Artist

Dr. Banting enjoyed painting as a hobby. Before his death in a plane crash, he was planning to dedicate much of his time to painting. Scroll down below to read a piece on Banting – Artist and Scientist. If you have a Banting painting and wish to share a picture on this site, please reach us via the Contact section.

Sir Frederick Grant Banting: Artist and Scientist

by Peter Myles Banting, Ph.D.

Fred Banting was born in 1891 and grew up on the family farm near Alliston, ON. He had two great passions: medical research and painting. He fought bureaucratic and financial obstacles to discover and prove that the hormone insulin could prevent certain death from diabetes. That breakthrough brought instant global fame and recognition to the modest and shy farm boy. He was the first Canadian to be awarded the Nobel Prize and was knighted Sir Frederick Grant Banting. After almost a century, insulin is still in widespread use and has saved more than 350 million people’s lives.

Fred continued his medical research, developing the first flight suit to prevent pilots under excessive G-forces from blacking out, studying antidotes against the wartime use of anthrax, fostering research by young doctors, surveying the state of medical research across Canada, studying silicosis, understanding the mechanism of drowning, and seeking a cure for cancer.

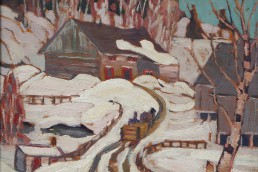

After winning the Military Cross in WW1, Dr. Banting set up private practice in London, ON. While waiting for the few patients to show up at his office, he began painting. He was interested in the work of the Group of Seven, and became friendly with them. It was Lawren Harris who nominated him to membership in the Arts and Letters Club in 1926. In 1927, A. Y. Jackson became Banting’s mentor. Together they went on extended sketching expeditions in Quebec, the Arctic and Greenland, Great Slave Lake and Skagway. It was no picnic. At times they struggled through snow drifts up to their waist, and painted with snow drifting into their sketch boxes and with hands and fingers so numb from cold that they could barely work. At other times the mosquitos were so thick that they became mixed in the oil paints. On one occasion Banting said: “And I thought this was a sissy game.”

Banting painted in many other parts of Canada, and in Europe. He executed fine drawings in pencil, charcoal and ink, worked in oil on wood and canvas, and issued serigraphs.

Sketches with fresh wet oils are difficult and clumsy to transport. Typically, the artist carries a bulky box with slots to keep the sketch boards separate. Banting, who was a pipe smoker, solved the problem by breaking wooden matches into five pieces. He imbedded them in the wet paint in the center and four corners of each sketch board, then tied the boards in a tight, compact bundle. Banting had critics who said insulin was a one-time flash in the pan. Despite his later scientific achievements, it certainly would be difficult for him to top that death-defying discovery. When he showed his bundled wet sketches to A.Y. Jackson, Banting said: “People who don’t like me say that after insulin I will never make another discovery. Well, how about this?” Thereafter, Jackson followed suit and bound his wet boards. Art and science coalesced.

A.J. Casson said: Banting “had one thing that’s important for a landscape painter – he had a feel … he was like the rest of us [in the Group of Seven] and painted what he had some heart and soul in.” In 2006, one of Banting’s 1937 paintings, St.Tîte des Cap, cost the buyer $43,125.

Tragically, on a WW2 medical research liaison mission to the U.K. in 1941, his sabotaged aircraft crashed near Musgrave Harbour, NL. Years before, Banting had told A.Y. Jackson that after he reached 50 he would like to devote all his time to art and leave research work to younger men. Ironically, he was 49 when he died.

He left both a scientific legacy that has allowed more than 300 million people to be alive today because they take insulin therapy, and an artistic legacy that has captured the beauty of Canada.