Questions and Answers about the Discovery of Insulin

Each and every historical record tells a story. However, some with important details are read too quickly. Then they get published or go up on the Internet, like this one, where they are accepted and passed along with the assumption that these records are perfectly correct. Here is an example. It is widely accepted in many published records that Frederick Banting came up with the idea which lead to the discovery of insulin late at night in London Ontario. Well did he? Or was the idea brewing in his head long before that one night?

Attached to this note is a record written by his cousin Fred Hipwell. They grew up together in Alliston Ontario, then went to the University of Toronto to become doctors. The record was written at the time of Fred Banting’s death. It tells a lot about the life and times of the man who had an idea which changed lives of all diabetic persons around the world. Except for one paragraph, which follows. It tells and slightly different story than the one found often on the Internet. As time moves along early records are often proven to be false.

“While reading a medical journal late one night, he had his vision of insulin. But early in 1918 he had discussed, with some of us in England, (after the Great War) the possibilities of such a substance and expressed his desire to do research on the pancreas. Perhaps the passing of a little child in diabetic coma back home in Alliston, when he as a boy had after all directed his future actions. This event affected him profoundly all the time”.

Dr. Joseph Applebe Gilchrist (1893 – 1951) was a classmate in Meds 1T7 at University of Toronto with Frederick Banting. The whole Gilchrist family were good friends and sometimes neighbours of the Bantings as they vacationed on a relative’s farm on the Scotch Line north of Alliston, Ontario. Here they are traveling together in Ireland. The picture was taken on the Giant’s Causeway in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. From Left To Right. Joe Gilchrist; Allan Cathbertson, a family friend, photographer and scribe; George Gilchrist; Mary Applebe Gilchrist; Essie Banting, Fred’s only sister; John Gilchrist; Joe Gilchrist; and George’s father.

Joe Gilchrist like many in the Meds 1T7 class, went off to serve in the Great War. Later in the war Joe came down with a case of the flu. That resulted in a case of diabetes. He was sent home to continue treatment. Like all diabetics at that time, his life outlook was bleak. His diabetes case is well documented in his WW1 service file, available on line.

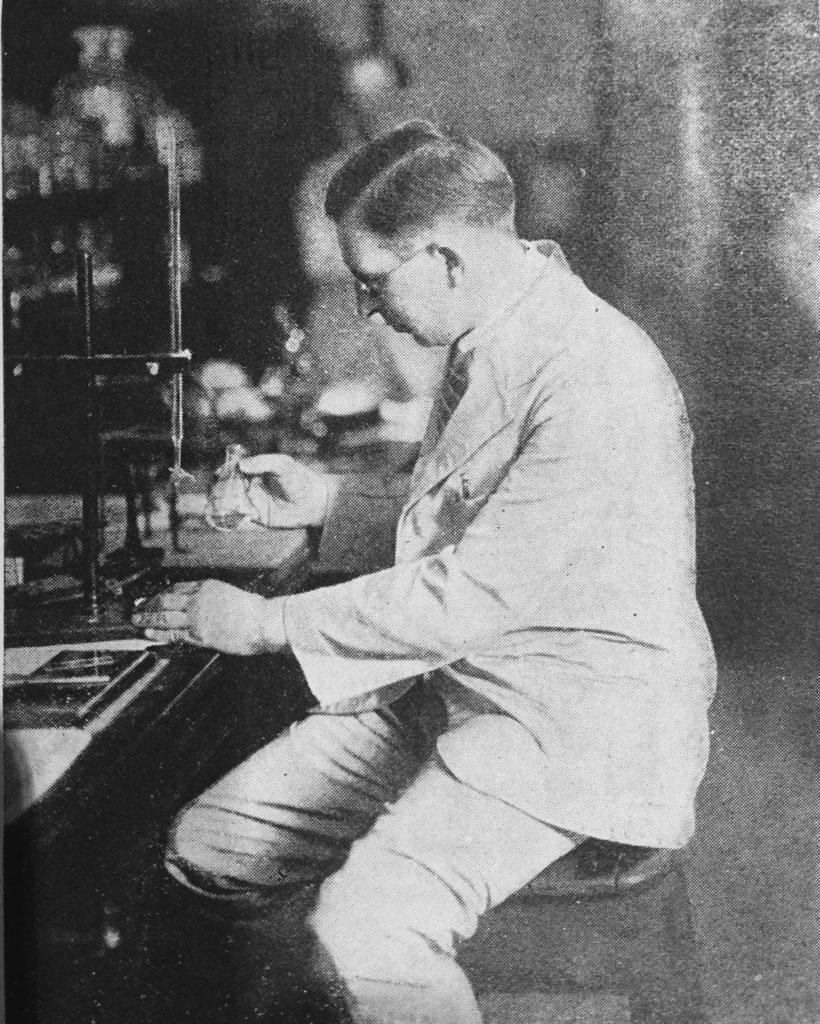

So Gilchrist was struggling and in the late fall of 1921 he found that his friend Fred Banting was working on a potential diabetic treatment in a laboratory at the Old University of Toronto Medical Building. He was the ideal person to try an experimenal treatment for his diabetes. Since Gilchrist was also a medical doctor, he could provide informed clinical feedback. He also had nothing to lose.

In the picture below we see Fred’s brother, Thompson Banting, Fred Banting, George Gilchrist and another of Fred’s brothers, Kenneth Banting, playing near the Boyne River in Alliston.

So Joe, pictured below, found his way to Banting’s lab and offered his services as a human test rabbit. In the first test, the experimental hormone that Banting called Isletin was given orally to Joe on December 20th 1921. There were beneficial results. It didn’t kill him either.

Prior to this, Banting and Best had tried Isletin on each other with no side effects other that a welt at the injection site.

The testing on Gilchrist continued. Interviews with Gilchrist about his experience were reported by Paul de Kruif in his book Men Against Death. Given enough time the crude drug worked on Joe Gilchrist. Fred Banting was in his Alliston home when the news arrived that Isletin doses had achieved successful results for Gilchrist. These experimental application of Isletin to Gilchrist have been called “the surreptitious test.” So Joe was the first diabetic person and the first doctor to receive Isletin, which later was renamed Insulin.

Fred Banting’s Great War service records, now available online, show that he was 5 ft – 11 inches, weighed 175 pounds and had light blue eyes. He was right-handed. He temporarily lost the use of right arm near the end of the war due to a shrapnel wound. He was injured when he was treating casualties close to the front line action. A piece of shrapnel, from an exploding shell, hit him on the inner part of his right elbow and upper arm. Despite his wound, Fred continued to help other injured soldiers for many hours. He remained at the front providing medical care even after he had been ordered to seek help for his own injury. That complicated his wound. When he returned to hospital from the front it was recommended that his right arm be amputated. He refused, and took over the management of the wound himself (picture below). He wrote many letters home while recovering. But he had to write them with his left hand. Fred had the scar from that severe wound for the rest of his life. For his bravery in action, Fred was awarded the Military Cross.

Some folks have described Fred’s posture as slightly stooped; and he was never considered a good public speaker. He had a good sense of humour and enjoyed pulling an occasional prank. For example, Fred was a regular smoker of Buckingham cigarettes. During a visit to the home of his friends the Hipwells, Fred flipped some cigarette ashes onto an overhead light fixture. Then he pointed out that it was dirty.

Fred was an accomplished artist. He painted many paintings on plywood panels using oils. He started this hobby while still living at home in Alliston. He did many sketches there. Later he became friends with the members of the Group of Seven, and went on sketching trips with A.Y. Jackson in Northern Quebec and the Yukon. Fred also did a lot of wood carving. The floor of his office often was littered with wood chips. A generous man, he never sold his art and gave most of his work away. Today his paintings are highly valued. At auction, one recently sold for many thousands of dollars.

Few know that Fred had a good baritone voice. He sang in his Alliston church choir. He was active in several Glee Clubs. He led many sing songs with his military buddies. He and Charles Best would sing together during their research work in 1921 and he did the same with A. Y. Jackson when they painted together.

As for his character, after Fred’s death his niece, Marion Walwyn gave a personal view in a March 6, 1941 interview: “Just over a year ago we talked together in London. He was the simple, kind, rather shy Fred. Exactly the same man Aunt Maggie (his mother) would have him be.” Fred was very close to his mother and wrote to her weekly.

Sir Frederick Grant Banting was born on a farm near Alliston Ontario on November 14,1891

in a simple farmhouse. This was a Gothic revival style, story and one half, farm cottage. These houses were featured in farm magazines of the day complete with building plans. It was located on Lot 2 Concession 2 of Essa Township, Simcoe County, Ontario, Canada. This is now the Banting Homestead, located about 90 kilometers north west of Toronto, Ontario. It was built in the year 1877 by the Meredith family, who were related to the Banting’s, when they moved out of their log cabin also located on the farm. Other houses just like it still survive in the area. They all have a distinctive central dormer often topped by a finial. The home was popular because the taxes on that style of dwelling were low. The Meredith’s added a back kitchen a couple of years later and this was the beginning of a long series of renovations, driven by expanding family needs. William Banting, Fred’s father, bought the house and the included 100 acre farm in the spring of 1891. Fred was born that fall. While the house no longer exists as it was in 1891, many remnants of it still remain. For example, the William Banting family dug under the house to build a cellar. They built a stone foundation under the house by working from the inside under the house Fred helped with this job. That foundation exists today as the current house rests on it. Many interior details also remain. Doors, built in cupboards, trim work from the old house can be seen inside the current house. Beyond the basement, the house was expanded by adding a section at the front and a large section at the back about 1903. That renovation was completely bricked. Fred describes the details of the old house right down to the room in which he was born in his memoirs and sketches. He described the house as an overlapper or clapboard clad. There is a picture of the house (this one) in his photo album.

Fred Banting was born in a room on the side, The house which heated by wood stoves must have been quite cold in 1891. But that cold day was the start of a medical miracle. The discovery of insulin has saved millions of lives world wide and this is ongoing.

Fred Banting’s interest in Canada’s native people was sparked during the time he was growing up on the Banting Homestead, the place of his birth in Alliston, Ontario. His father, William Banting, purchased the farm in 1891. An early Paleo-Indian hunting ground was discovered on his land. From the time Fred was old enough to play and work in the rich farm fields he became aware that the horse-drawn farm plows often would turn up artifacts from a long-ago era. The Banting’s collected these treasures when they were uncovered. In later years, the Royal Ontario Museum conducted an archeological dig on the farm property and examined many of the relics. The ROM determined that Paleo era people had camped on a glacial drumlin hill on the property. These Paleo people, from 20,000 years ago had selected this to be their camping spot because it was an island in the middle of glacial Lake Algonquin. The island land mass was formed by melting glaciers and the farmland that yielded the relics was actually the bottom of the lake. The relics were predominately spearheads and the carving tools that were used to make them.

While growing up, young Fred often would go digging in an island in the nearby Boyne River. He called it Scout Island. Fred and his cousin Fred Hipwell probably dug up most of that place looking for buried treasure. Hipwell and Banting eventually graduated in the same medical class at the University of Toronto.

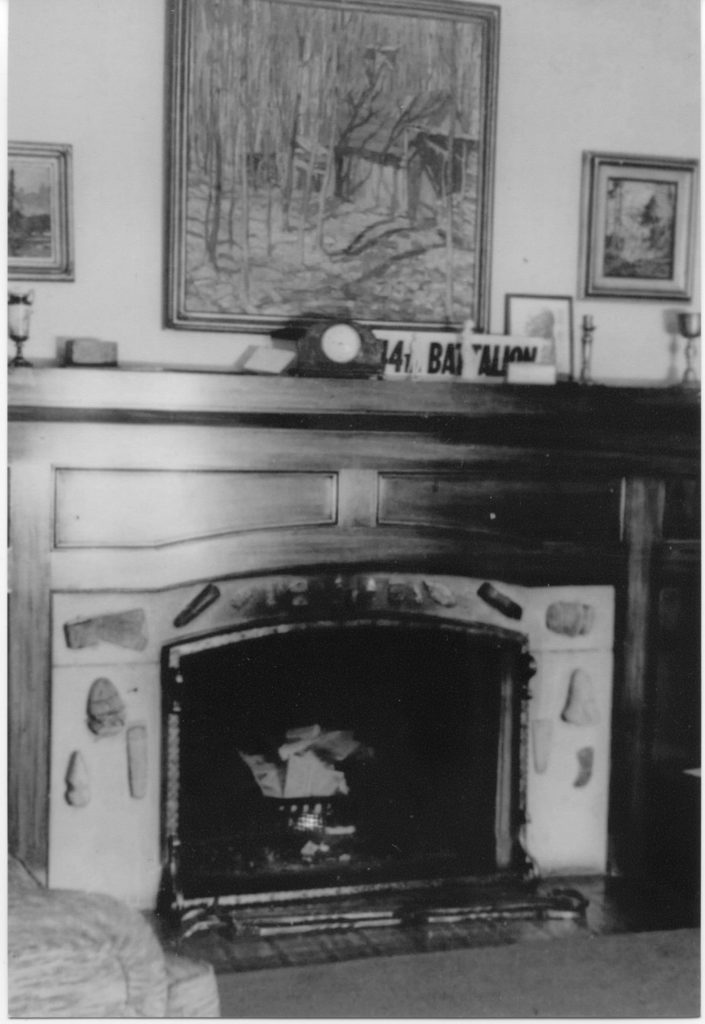

Fred’s interested in this continued into his adult life. When he built his second home in Toronto at 205 Rosedale Heights Fred built a selection of these relics into his new fireplace. A picture of the fireplace is shown above. Note Banting’s war memorabilia and oil paintings over the fireplace. These are now gone as the fireplace was updated later by a contractor.

Fred’s interested in this continued into his adult life. When he built his second home in Toronto at 205 Rosedale Heights Fred built a selection of these relics into his new fireplace. A picture of the fireplace is shown above. Note Banting’s war memorabilia and oil paintings over the fireplace. These are now gone as the fireplace was updated later by a contractor.

Fred’s interest in aboriginal people grew during a sketching trip to the Canadian Arctic with the prominent Canadian artist A. Y. Jackson. Many photographs were taken of the artistic pair on the Beotic, the research vessel on which they were passengers.

Another trophy of his trips to the native areas of Canada is a kayak that is on display in his home Town, Alliston, at the Museum on the Boyne.

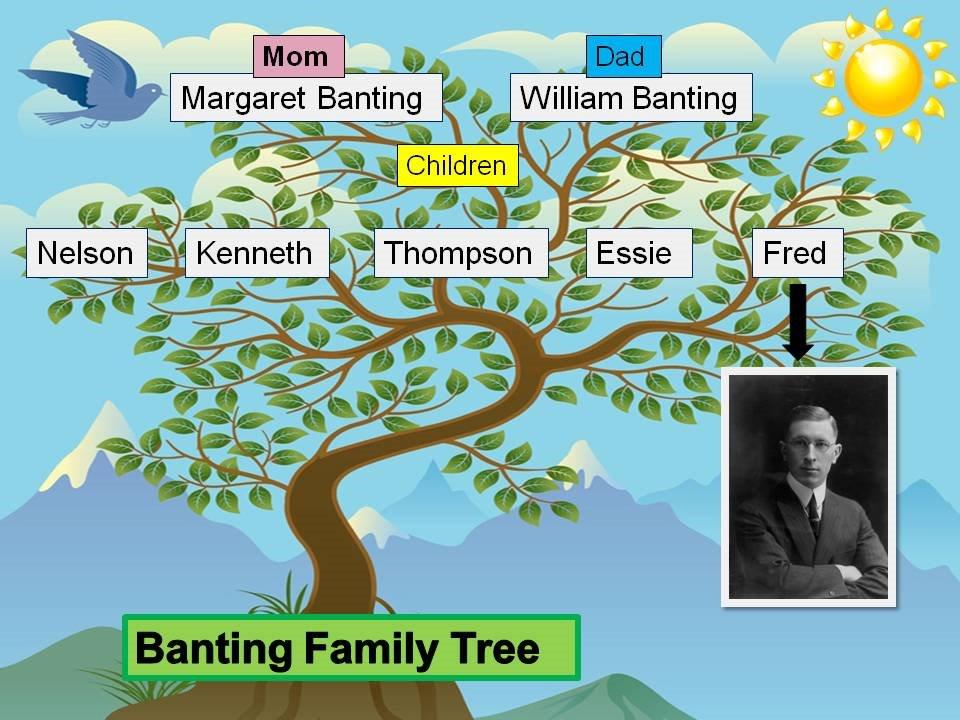

Edward Banting, Fred’s nephew was the Banting family tree genealogist. He produced extensive family trees for both his grandparents William Banting and his wife Margaret Grant. They were Fred’s parents. He did this extremely accurate work the hard way without a computer or the internet. His work has now been computerized and extended. Many Bantings in Canada, England, USA, Australia and other countries are now proven relations by using DNA technology. There is a branch of the tree connected to the United Empire Loyalists via Margaret Grant.

Yes. Of course.

We welcome your input. Please send messages to the email address posed below. We look forward to posting selected messages.

By the way, Sir Frederick Banting hated to be called “Sir.” He would have appreciated you addressing your message to “Dear Fred.” Please do. Here is our email address – fgb at discoveryofinsulin.com.

Fred Banting was on his way to England, to do work that he hoped would shorten World War II when he died in an airplane crash. The aircraft was a Lockheed Hudson MK IV. It had arrived in Canada after being manufactured in Burbank California.

Fred got on the plane in Montreal and flew to the Newfoundland Airport, in what now is called Gander. The pilot was Joseph Creighton Mackey, an American. William Bird, from Kidderminister, England was the navigator. William Snailham, of Halifax was the radio operator. After delays on departure due to bad weather, Hudson T-9449 along with other Hudsons being ferried to England took off from the island airport.

Banting’s plane took off early Thursday morning on February 20, 1941. An hour later the left engine failed and Mackey decided to return. They approached land not far from a fishing village called Musgrave Harbour. But at that point the other engine failed. They were about 40 miles from the airport they had just left. Mackey tried his best to do a “dead stick” landing, hoping to find a frozen lake as they approached land. They almost made it safely; but on approach the left wing struck a very large tree. Abruptly the plane swung about 110 degrees from its flight path, stalled, and settled on a swath of trees beside a large snow covered lake. The lake now is called Banting Lake. Banting and Mackey were badly injured, but Bird and Snailham were killed instantly. Fred died the next day, the result of a punctured lung. He died in uniform, a Major, in service of his county.

The picture below shows the crash site many years later. The area was completely burned over by a forest fire. Banting Lake is at the bottom of the picture and the plane was traveling from the middle top to middle bottom of the photo. The site is SSW of Musgrave Harbour. Today it is marked by a monument,

Musgrave Harbour honours Banting with a camping park, walking trail, named after him, along with a granite monument and full size replica of Hudson T-9449.

Each and every historical record tells a story. However, some with important details are read too quickly. Then they get published or go up on the Internet, like this one, where they are accepted and passed along with the assumption that these records are perfectly correct. Here is an example. It is widely accepted in many published records that Frederick Banting came up with the idea which lead to the discovery of insulin late at night in London Ontario. Well did he? Or was the idea brewing in his head long before that one night?

Attached to this note is a record written by his cousin Fred Hipwell. They grew up together in Alliston Ontario, then went to the University of Toronto to become doctors. The record was written at the time of Fred Banting’s death. It tells a lot about the life and times of the man who had an idea which changed lives of all diabetic persons around the world. Except for one paragraph, which follows. It tells and slightly different story than the one found often on the Internet. As time moves along early records are often proven to be false.

“While reading a medical journal late one night, he had his vision of insulin. But early in 1918 he had discussed, with some of us in England, (after the Great War) the possibilities of such a substance and expressed his desire to do research on the pancreas. Perhaps the passing of a little child in diabetic coma back home in Alliston, when he as a boy had after all directed his future actions. This event affected him profoundly all the time”.

Lockheed Hudson T 9449 crashed about 10 miles south of Musgrave Harbour Newfoundland and Labrador on the evening of February 20, 1941 carrying Sir Frederick Banting as a passenger. Few pictures on line show the extensive damage to the plane. The seasoned pilot Joe Mackey almost made a successful ditching of the plane in deep snow on what is now called Banting Lake. The warplane struck a large tree on the edge of the lake causing extensive damage to the left wing. Hitting the tree caused an immediate left hook and sudden stop. Those aboard were thrown about the craft. Two airmen died instantly. Here is a picture of the left wing damage. The glazed nose, the bomb aimer and navigator’s position, was also extensively damaged. Fred Banting died the next day and a result of a punctured lung. Mackey survived.